Researchers have identified new compounds that inhibit blood clotting. Blood clots can lead to heart attack and stroke, which has driven interest in clot-busting agents. Athan Kuliopulos and colleagues at Tufts University in Boston found that in mice, the new compounds prolong the amount of time that the animals bleed, indicating that clotting is quenched. In a test tube, the new compounds inhibit aggregation of human platelets, which is necessary for the formation of a blood clot. The compounds have not yet been tested in people. But if they work as well as they do in a test-tube and in mice, they have the potential to add to the arsenal of drugs that keep the blood thin.

The compounds, peptides called pepducins, work in a unique way. Over 50% of prescribed drugs target one class of protein in the human body - G-protein coupled receptors. These drugs include antihistamines, beta blockers, and pain relievers such as morphine. The pepducins also target G protein coupled receptors. But pepducins do it by crossing the biological membrane and freezing the receptors up from the inside. In contrast, all known drugs hit the outside of these receptors.

In this study, platelet aggregation was inhibited through G protein coupled receptors that stud the platelet membranes. Pepducins show promise as general inhibitors of G protein coupled receptors, and there are over 1000 G protein receptors in the human body. Some of them are receptors waiting for a drug - perhaps a pepducin.

DIABETES DRUGS SHOW THEIR WEIGHT

In the last couple of years a new class of drugs have become commonly prescribed for diabetes, called TZDs. But they've also come with problems, among them side effects such as excess weight gain. And, their precise mechanism of action has remained largely a mystery. New research sheds light on both the heavy side effect and the mechanism of action.

The key, it seems, is fat cells. Researchers at the University of Pennsylvania and Duke University Medical Center found that TZDs encourage fat cells to take up the building blocks of fat from the bloodstream. These building blocks, called fatty acids, are then converted in fat cells to triglycerides, the whitish substance we all recognize as fat. So, TZDs make fat cells make fat - hence the side effect. But TZDs also remove fatty acids from the blood stream. It's known that fatty acids in the bloodstream are associated with a blunted sensitivity to insulin that accompanies diabetes. So, by sucking fatty acids out of the blood stream, TZDs may be making the body more sensitive to insulin.

Prior to this study, it was not known how TZD plumped up fat cells. Now it's clear that the cells are actually synthesizing fat from its building blocks. That challenges the long-held scientific viewpoint that fat cells did not have the enzymes to put the pieces together.

Whether the fatty acid vacuum system is the main secret of TZDs diabetes-fighting ability is not known. But the new data may help scientists design ways to minimize side effects while boosting the effectiveness of this class of drugs.

Ultimi Articoli

Neve in pianura tra venerdì 23 e domenica 25 gennaio — cosa è realmente atteso al Nord Italia

Se ne va Valentino, l'ultimo imperatore della moda mondiale

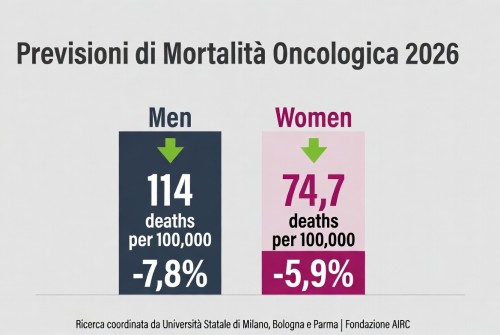

La mortalità per cancro cala in Europa – tassi in diminuzione nel 2026, ma persistono disparità

Carofiglio porta — Elogio dell'ignoranza e dell'errore — al Teatro Manzoni

Teatro per tutta la famiglia: “Inside and Out of Me 2” tra ironia e interazione

Dogliani celebra quindici anni di Festival della TV con “Dialoghi Coraggiosi”

Sesto San Giovanni — 180 milioni dalla Regione per l’ospedale che rafforza la Città della Salute

Triennale Milano — Una settimana di libri, musica, danza e arti sonore dal 20 al 25 gennaio

A febbraio la corsa alle iscrizioni nidi – Milano apre il portale per 2026/2027