Fanconi anaemia (FA) is a rare autosomal recessive disease that is characterized by congenital abnormalities, progressive bone-marrow failure and cancer susceptibility 1,2. Children with FA frequently develop PANCYTOPAENIA during the first decade of life, and death often results from complications of bone-marrow failure. Although FA has an incidence of less than 1 per 100,000 live births, a molecular understanding of the FA pathway might have relevance to other types of cancer. The recent cloning of seven FA genes has improved the prospects for diagnosis and therapy, and has elucidated the mechanisms of chromosome instability in this cancer.

The clinical features of FA have been extensively reviewed. These include skeletal abnormalities (that is, thumb or limb abnormalities) and abnormal skin pigmentation (that is, hypopigmentation or cafè au lait spots) 3. Other organ systems that are involved include the cardiac, renal and gastrointestinal systems, and individuals with FA have decreased fertility. Accordingly, the FA genes are necessary for the normal development of several organ systems.

The haematological consequences of FA often develop in the first few years of life. Anaemia and thrombocytopaenia (decreased platelet count) often proceed the neutropaenia (decreased white-cell count). FA patients also develop clonal chromosomal abnormalities in the bone-marrow progenitor cells (that is, chromosome 1 or 2 abnormalities or monosomy 7), and these can develop into myelodysplasia or acute myeloblastic leukaemia (AML). FA is considered to be a genetic model system for the study of myelodysplastic syndrome or myeloid leukaemia.

FA patients are predisposed to many types of cancer 4. Although AML is the most common cancer in these patients, older patients can develop squamous-cell carcinomas of the head and neck or gynaecological system. Recent studies have indicated a high incidence of oesophageal cancer in FA patients who have received a bone-marrow transplant 5.

FA ”€ like other rare, inherited cancer-susceptibility syndromes ”€ has provided important insights into the genetic basis of cancer in the general population. The FA-associated gene products ”€ along with BRCA1 and BRCA2 ”€ have been found to function in a common pathway that regulates the cellular response to DNA damage. Inherited defects in this pathway underlie the chromosomal instability and drug sensitivity of at least a subset of solid tumours in the general (non-FA) population. Strikingly, the FA/BRCA pathway has numerous molecular interactions with other proteins that are known to mediate checkpoint responses, such as ataxia telangiect asia mutated ( ATM ) and Nijmegen breakage syndrome 1 ( NBS1 ), as well as the DNA-repair response protein RAD51 .

Cellular phenotype of FA

Many phenotypes have been reported to characterize cells from patients with FA 6(Box 1 ). The most consistent of these phenotypes is hypersensitivity to agents that produce interstrand DNA crosslinks, such as mitomycin C, diepoxybutane and cisplatin. After treatment with crosslinking agents, FA cells have increased chromosome breakage, RADIAL CHROMOSOMES and other cytogenetic abnormalities that occur during metaphase. Crosslinker hypersensitivity can result in apoptosis or growth arrest, depending on the cell type. FA cells also have more modest hypersensitivity to other DNA-damaging agents, such as ionizing irradiation and oxygen radicals.

A second phenotype of FA cells is an increase in the proportion of cells with 4N DNA content 7,8. This indicates that a G2/M or late S-phase delay occurs in the cell cycle 9. The increase of cells with 4N DNA content can occur spontaneously in some FA cells, but becomes much more pronounced after treatment with crosslinking agents. Some reports indicate that FA cells have primary defects in signalling and apoptosis induction pathways. The relationship of these other phenotypes to DNA damage is less clear.

The hypersensitivity of FA cells to DNA crosslinking agents, such as diepoxybutane and mitomycin C, provides a convenient diagnostic test for the disease 10 . The diepoxybutane chromosome breakage test, which is performed on peripheral-blood lymphocytes, remains the clinically certified diagnostic tool for FA. The diepoxybutane test can also be performed on primary fibroblast cultures. As several FA genes have been cloned, direct sequencing of the genes can be used in prenatal diagnosis. More recently, the ability to complement cells from FA patients with retroviral vectors that encode FA-associated genes, along with the development of immunoblots for FA proteins, have improved the ability to diagnose this disease and to determine the subtype 11-13 .

Treatment of FA

The treatment of FA is largely directed towards the complications of bone-marrow failure. Some FA patients respond initially to haematopoietic growth factors, such as erythropoietin and granulocyte”€œmacrophage colony-stimulating factor 14 . Others respond to androgen therapy, although long-term androgen exposure might result in liver disease. The best treatment for pancytopaenia that is associated with FA is matched allogeneic bone-marrow transplantation. In the absence of a histocompatible matched sibling, unrelated donor transplants 15 and cord-blood transplants 16-18 are also routinely performed. In addition, new approaches involve pre-implantation genetic diagnosis 19 and gene therapy 20 ,21 for select patients with FA. FA patients who survive bone-marrow disease remain prone to malignancies that usually occur in the second or third decade of life. Early surgical excision of these tumours is crucial, as FA patients experience toxic side effects after chemotherapy or radiation therapy.

Genetics

Cell-fusion experiments have shown the existence of at least eight separate FA COMPLEMENTATION GROUPS . These are FA-A, B, C, D1, D2, E, F and G. So far, seven FA genes have been cloned 22-26 . The genes are not clustered, but are instead widely dispersed throughout the genome ( Table 1 ). In most cases, these genes were cloned by functional complementation of mito-mycin-C-sensitive cells with cDNAs ( FANCC ,A,G,Fand E, in chronological order). Two of the genes were isolated by positional cloning approaches ( FANCA and FANCD2 )27 ,28 . Complementation groups A ( 65%), C (15%) and G (10%) account for most FA patients in most populations. Some ethnic groups have a higher occurrence of specific mutations that account for most cases in these populations. The FANCC IVS4 +4 A Tallele is prevalent among Ashkenazi Jews, with a carrier frequency of about 1 in 150 (Refs 29 ,30 ). Similarly, FANCA mutations are common in the Afrikaners of South Africa, due to a FOUNDER EFFECT .

Overall, FA is genetically heterogeneous, and many mutations have been found in each complementation group. There is only a modest correlation between phenotype and subtype. Hearing deficits, for example, are found more commonly in patients with mutations in FA-G . Also, patients with FA subtypes C or G tend to have earlier onset of bone-marrow failure and haematological malignancies, compared with patients who have mutations in FA-A 31 . Nonetheless, the complete spectrum of phenotypic variation can be found within single complementation groups, and certain phenotypes can be correlated strongly with specific mutations. For example, patients that are homozygous for the FANCC IVS4 +4 A Tmutation develop severe FA, with a high frequency of birth defects and early onset of the anaemia 32 . By contrast, patients that are homozygous for the FANCC 322 Gmutation have comparatively few birth defects and develop anaemia later in life 32 .

FA protein interactions

The first six FA genes that were cloned have no sequence similarity to each other or to other known DNA-repair genes. Of these genes, only FANCD2 has homologues in other eukaryotic species, including Drosophila melanogaster ,Caenorhabditis elegans ,Arabidopsis thaliana , Fugu and zebrafish 28 ,33 . This indicates that FANCD2 has an important conserved cellular function. As the biallelic disruption of any one of these six FA genes results in similar cellular and organismal phenotypes, investigators proposed that the six proteins cooperated in a cellular pathway 34 ,35 .

A multisubunit nuclear complex. Biochemical studies indicated that the FANCA and FANCC are part of the same complex 36 , although they have not been shown to interact directly in vitro . This interaction might require additional proteins, as it has been shown to require expression of FANCG 37 . FANCA and FANCC failed to co-immunoprecipitate from lysates of FA cells that are derived from complementation groups B, E and F 38 ,39 , indicating that several FA proteins are probably required to form the complex. The direct binding interactions among some FA proteins were further confirmed by two-hybrid analyses 40 (Fig. 1 ). Loss of one FA protein, such as FANCA or FANCG, resulted in instability of the FA complex and a decreased half-life of newly synthesized FA proteins 41 . The FA protein complex was, however, detected in cell lines derived from other FA complementation groups, such as the D1 and D2 groups. These results indicated that the protein products of the D1 and D2 genes are not required for protein-complex assembly. The FA complex seems to have some chromatin binding activity, which is enhanced by exposure to crosslinking agents 42 . Recent evidence indicates that the FANCE protein might interact with FANCD2 (Ref. 43 ), although FANCD2 is not an integral component of the FA complex 44 .

Figure 1- |- The Fanconi anaemia/BRCA pathway.

Several FA proteins, including A, C, E, F and G, form a constitutive complex in the nucleus of normal human cells. In response to DNA damage, or during the S phase of the cell cycle, this complex mediates the monoubiquitylation (Ub) of FANCD2 at lysine 561 (K561). Activated FANCD2, in turn, is translocated to chromatin and DNA-repair foci. These foci contain the BRCA1 protein and the BRCA2”€œFANCD1 protein complex. BRCA2/FANCD1 is known to bind directly to RAD51 and to DNA, and to participate in homology-directed DNA repair. Taken together, the model indicates that the FA/BRCA pathway regulates DNA repair.

Although the FA proteins form a multisubunit complex, the function of the complex remains unknown. More research is required to determine whether the complex plays a direct role in sensing DNA damage, repairing DNA damage or stabilizing chromosome structures. None of the FA proteins in the complex has an obvious catalytic domain and, so far, no enzymatic activity has been associated with the purified complex. The FA complex might be an indirect upstream regulator or sensor in the DNA-damage response.

The FANCD2 protein. The FANCD2 protein seems to function at a downstream point in the FA pathway 45 (Fig. 1 ). Initial studies indicated that the FANCD2 protein exists in two cellular isoforms: FANCD2-S (the primary unmodified translation product) and FANCD2-L (the monoubiquitylated isoform). Importantly, the FANCD2-L isoform is only observed in wild-type or complemented FA cells that are resistant to mitomycin C. This finding indicates that the FA complex and all of the FA subunits therein are required for the conversion of FANCD2-S to FANCD2-L. Mass spectrometric analysis showed that this modification is a monoubiquitylation of FANCD2 on Lys561 (K561). Mutation of this lysine residue to arginine ablates monoubiquitylation, indicating that other lysine residues in the protein cannot substitute as sites of ubiquitin attachment. This lysine (K561) is also conserved in many lower eukaryotic FANCD2 homologues 28 , further supporting its crucial function.

The conversion of FANCD2-S to FANCD2-L is required for DNA-damage-inducible changes in FANCD2 localization. Monoubiquitylated FANCD2 is targeted to subnuclear foci, where it co-localizes with BRCA1 (Ref. 45 ) and RAD51 (Ref. 46 ). FANCD2 foci do not form in FA cells of subtypes A, B, C, E, F or G, but do assemble in complemented cells. Importantly, FANCD2 monoubiquitylation and targeting to foci is induced by either DNA-damaging agents such as ionizing radiation, ultraviolet light or mitomycin C, or during the S phase of the cell cycle. This damage-inducible response indicates that the activated FANCD2 protein might interact with other DNA-damage-response proteins that are known to be associated with BRCA1 foci 47 .

Interaction with BRCA proteins. Several lines of evidence have indicated that FANCD1 might be related to BRCA1 and BRCA2. Disruption of BRCA1 results in loss of DNA-damage-inducible FANCD2-containing subnuclear foci. BRCA1 might therefore regulate the assembly of these foci 45 . Consistent with this, the BRCA1 protein contains a RING-FINGER DOMAIN , which is commonly observed in some E3 ubiquitin ligases. BRCA1 might therefore ubiquitylate FANCD2 in vivo 48 .BRCA1 -/- or BRCA2 -/- cells also show mitomycin C hypersensitivity and chromosome instability 49 , similar to the defects observed in FA cells. Functional complementation of BRCA2 -/- cells with wild-type mouse Brca2 restores mitomycin C resistance 50 , and targeted inactivation of the Brca2 gene (by disrupting the region that encodes the carboxyl terminus but not the amino terminus) results in viable mice with a FA-like phenotype. Features of this phenotype include small size, skeletal defects, hypogonadism, cancer susceptibility, chromosome instability and mitomycin C hypersensitivity 51 .

To investigate the relationship between BRCA genes and FA, the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes were sequenced in cells from FA-B ,FA-D1 and unassigned FA patients 52 . Although no BRCA1 mutations were detected, biallelic mutations in BRCA2 were observed in these cells. The most common BRCA2 mutations observed were frameshift mutations in the 3' region of the gene, which would be predicted to cause truncations of the carboxyl terminus. Indeed, BRCA2 proteins with carboxy-terminal truncations were detected in cell lines derived from some patients with FA. These mutant BRCA2 proteins might have partial activity. Functional complementation of FA-D1 fibroblasts with wild-type BRCA2 cDNA restored mitomycin C resistance, indicating that FANCD1 is identical to BRCA2.

Paradoxically, cell lines derived from a patient in the FA-B complementation group also contained two mutant BRCA2 alleles. One mutant allele contained a frameshift mutation in exon 11, and the second allele contained a polymorphic stop codon in exon 27. The FA-D1 and FA-B cells have biallelic mutations in the same gene ( BRCA2 ), indicating intragenic or interallelic complementation. Alternatively, the protein product of some mutant BRCA2 alleles might have dominant activity in vivo , accounting, at least in part, for these discrepancies.

Regulation of the FA/BRCA pathway

Individuals with biallelic BRCA2 mutations share clinical features with other FA patients. These include congenital abnormalities, abnormal skin pigmentation, bone-marrow failure and cellular sensitivity to mitomycin C. These similarities indicate that BRCA2 and other FA proteins cooperate in a common DNA-damage-response pathway ( Fig. 1 ). According to this model, DNA damage activates the monoubiquitylation of FANCD2, which targets it to DNA-repair foci that contain BRCA1 and BRCA2. Previous studies have indicated that FANCD2 is not monoubiquitylated in mutant FA-B cells, whereas it is in mutant FA-D1 cells. BRCA2 might therefore function upstream in the pathway, by promoting FA-complex assembly and FANCD2 activation, and/or downstream in the pathway, by transducing signals from FA proteins to RAD51 and the homologous recombination machinery. Formation of RAD51-containing foci seems to be reduced in some FA cell lines, such as mutant FA-D1 fibroblasts 53 . This indicates that the FA pathway might be required for the organization of RAD51 into functional DNA-repair units. The precise molecular function(s) of BRCA1 and BRCA2 in this pathway remain to be elucidated.

A less likely scenario is that BRCA2 functions independently of the FA pathway, and that disruption of BRCA2 phenocopies the disruption of the FA-associated genes. Patients with FA that also have BRCA2 mutations seem to have a more severe clinical phenotype, with earlier onset of myeloid leukaemia and other malignancies. Whether FA patients with BRCA2 mutations have other unique developmental abnormalities has not been determined, due to the small number of patients.

Other unresolved questions arise from the model that is proposed in Fig. 1 . First, little is know about the exact molecular mechanism of FANCD2 monoubiquitylation. Although the FA complex is required for this modification, none of the known FA proteins have a catalytic domain of a ubiquitin ligase. Ubiquitin ligases often contain ring fingers that are homologous to E6-AP carboxyl terminus (HECT) DOMAINS . As BRCA1 co-localizes with activated FANCD2, BRCA1 or BARD1 (BRCA1-associated ring finger E3 ubiquitin ligase) could serve this function. Consistent with this idea, the BRCA1 protein interacts with FANCA ”€ one of the subunits of the FA-protein complex 54 . Alternatively, the RAD6 ”€œRAD18 complex, which monoubiquitylates histones 2A and 2B, might function as a ubiquitin ligase for FANCD2. It will be important to determine whether BRCA1 or BARD1 can monoubiquitylate FANCD2 in vitro , and whether cells that are deficient in these E3 ring-finger ligases have decreased levels of FANCD2-L.

Recent studies indicate that monoubiquitylation is crucial for the association of FANCD2-L with damaged chromatin 55 . A mutant form of FANCD2 that fails to undergo monoubiquitylation (FANCD2-K561R) remains in the soluble nuclear fraction and fails to bind chromatin. The molecular basis for this targeting remains unclear, but indicates that some sort of monoubiquitin receptor could be present at sites of DNA repair.

Finally, several other aspects of the FA pathway remain unclear. First, additional regulatory enzymes modulate the pathway. For instance, ubiquitylation events are often preceded by phosphorylation events. As FANCD2 is monoubiquitylated following DNA damage or during S phase of the cell cycle, different kinases might phosphorylate FANCD2 near lysine 561 to activate its monoubiquitylation. Also, precursor/product analysis reveals that the monoubiquitylated form of FANCD2 is recycled back to the unubiquitylated isoform. So, a deubiquitylating enzyme could function to convert FANCD2-L to FANCD2-S during the mitotic phase of the cell cycle 46 . Deubiquitylating enzymes are a relatively new family of regulatory enzymes, and their specific substrates are unknown 56 .

FA and ATM kinase

In addition to their mitomycin C sensitivity, FA cells also show hypersensitivity to ionizing radiation 57 ,58 , indicating that the FA pathway might interact with the kinase ATM. Ataxia telangiectasia (AT) is another autosomal recessive human disease that results in spontaneous chromosome breakage and haematological cancers 59 . Unlike FA patients, AT patients have immunodeficiency and progressive cerebellar neural degeneration. AT cells are hypersensitive to ionizing radiation but are not hypersensitive to crosslinking agents. The ATM gene encodes an ionizing-radiation-activated protein kinase that phosphorylates and activates proteins that are involved in cell-cycle checkpoint responses, including p53 (Refs 60 ,61 ), CHK2, Nijmegen breakage syndrome (NBS1) 62 ,63 and BRCA1 (Ref. 64 ). Many of these proteins cooperate in the ionizing-radiation-activated S-phase checkpoint response. Biallelic loss of ATM or its substrates results in a defect in the ionizing-radiation-activated S-phase checkpoint.

Interestingly, cells that are derived from patients with the FA-D2 subtype, but not from other subtypes, have a similar defect in the ionizing-radiation-inducible S-phase checkpoint, indicating possible molecular interactions between ATM and FANCD2 (Ref. 65 ). Further studies indicated that, in response to cellular exposure to ionizing radiation, the ATM directly phosphorylates FANCD2 on serine 222, as well as on other sites ( Fig. 2 ), and this is required for the establishment of the S-phase checkpoint. A mutant form of FANCD2 (FANCD2-S222A) that is not phosphorylated by ATM fails to activate the checkpoint in transformed human fibroblasts. Transfection of the mutant FANCD2 (S222A) into wild-type cells induces an S-phase checkpoint defect, which is characterized by persistent DNA synthesis even after cellular exposure to ionizing radiation (K. Nakanishi and A. D'Andrea, unpublished observations). This defect in the intra-S-phase checkpoint has been observed in human SV-40 transformed FA-D2 cell lines and has not been confirmed in mutant FA-D2 primary fibroblasts.

more info ->>

Ultimi Articoli

Neve in pianura tra venerdì 23 e domenica 25 gennaio — cosa è realmente atteso al Nord Italia

Se ne va Valentino, l'ultimo imperatore della moda mondiale

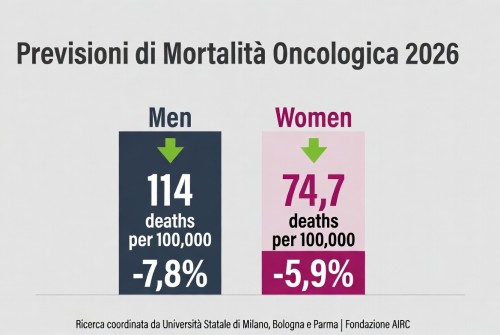

La mortalità per cancro cala in Europa – tassi in diminuzione nel 2026, ma persistono disparità

Carofiglio porta — Elogio dell'ignoranza e dell'errore — al Teatro Manzoni

Teatro per tutta la famiglia: “Inside and Out of Me 2” tra ironia e interazione

Dogliani celebra quindici anni di Festival della TV con “Dialoghi Coraggiosi”

Sesto San Giovanni — 180 milioni dalla Regione per l’ospedale che rafforza la Città della Salute

Triennale Milano — Una settimana di libri, musica, danza e arti sonore dal 20 al 25 gennaio

A febbraio la corsa alle iscrizioni nidi – Milano apre il portale per 2026/2027